I have copied and pasted Sandra's email for all of her recommendations for this weather (January 2024)

Here are the recommendations from 2 people I consider to be expert with regard to what to do when the weather gets cold:

#1.

I don't get too concerned if it's just one night for an hour or so, but when it's nights in a row and the days don't get hot enough to warm things backup, I start moving things into my protected back porch and when I run out of room into the house.

My rule of thumb is when under 55 degrees I start to be concerned about my vandas, cane dendrobiums and brassovolas. I don't grow grammatophyllums anymore but they don't like the cold either. Under 50 degrees I start to be concerned about the few phals I have, my maxillarias (coconut orchids), my encyclias and then start taking a look at my non-orchid plants.

I'm sure there are some exceptions, but generally your cattleyas and oncidiums will be fine.

Don't get confused about your dendrobiums and bring everything in, your nobile dens, pendant dens and den. aggregatum (lindleyi) need the cold to bloom.

If growing on trees, the trees help to keep them warm.

If you plan on covering things instead of bringing them in, do not use plastic. When the sun come out you can easily burn your plants.

You will know you have cold damage in about a week after the cold, leaves will turn yellow and start dropping. If you see leaves turning purplish or reddish that is a sign of a magnesium deficiency. If this happens, use potassium nitrate mixed with Epson Salts (1 tablespoon of each per gallon). The Epson Salts will provide the needed magnesium to green them back up. We have plenty of potassium nitrate in stock.

#2

Plants in good nutritional health will tolerate cold temperatures better and recover from injury faster than plants grown with suboptimal or imbalanced nutrition.

Methods of Protection

Plants can be moved into the house or to protective structures where there is more protection from the cold. If this is not an option, determine in advance which plants are most valuable to you. It is not a bad idea to mark those with a colored label or keep them all in a particular spot. That way, if you do need to gather them quickly, you will not be searching through perhaps hundreds of plants and labels to find them.

Also note which orchids in your collection hate cold. Many commonly grown orchids tolerate winter temperatures of about 55° F (13° C) at night, including some hardier Vandas, Stanhopeas, Oncidiums, some Dendrobiums, Cattleyas, Catasetums and cool-growing Paphiopedilums. Most Cymbidiums can take winter night temperatures in the 40's (4° C), and many need such a stimulus to bloom well.

White or yellow Vandas, as well as some Dendrobiums (Phalaenopsis-type, latouria, and antelope-type), are especially sensitive and do not like temperature drops below 60° F (16° C); they can be particularly prone to losing leaves when exposed to cold temperatures. Cattleyas tend to be more hardy and can tolerate lower temperatures better. The violaceas and dowiana cattleyas are more sensitive and need to be protected.

Grammataphyllums, Phalaenopsis, and Bulbophyllums are also very sensitive to cold and need to be protected. I know that many of you have very large Grammies. Try to cover them with a sheet or even newspaper to hold in the heat. If you have your led Christmas lights still available, you can wrap you large plants in them and cover with a sheet. It will keep them several degrees warmer!

Many of you have your orchids in trees and cannot move them. Trees are large heat sinks and so the roots and stems will stay warmer than those in pots, and the canopy protects the heat from escaping. So those plants will fair better.

It's important that the plants are fully dry before the cold hits. Moisture on the leaves will evaporate to the dew point which usually is much colder than the air, so you want your plants to be dry. We suggest not watering during this cold time. If you have automatic irrigation, turn it off until the cold is over.

Have wraps, clothespins, sheets, etc ready to cover smaller plants. Many materials can be used as insulating wraps. Frost cloth, available at most hardware stores, is lightweight and traps heat, but is designed to breathe as well. Sheets, blankets, towels, burlap and other coverings can also be used. We do not recommend using plastic.

If you have plants around a pool, you can run the filter all night. The turbulence from the water can generate heat transfer to the air for more warmth.

After the Fact

The effects of cold damage are not always immediate. A hard freeze, which we will not have, has immediate effects. But stress from long term cold weather, which we will have, may take weeks to see the full damage. After the last cold spell we had, the first thing I noticed, after a few days, was yellowing of the lower vanda leaves and discoloration on the Grammataphyhllums.

The positive side of the occasional winter chill is that, in many cases, cool periods help induce or enhance bud initiation and flowering. It also helps to promote dormancy in deciduous orchids.

Keep in mind that there are other cold sensitive plants that need to be protected like anthuriums, alocasias, medinillas and some other very tropical plants. If you have them in a pot, bring them into a protected place and, if not, cover them with a blanket, sheet, towel etc as suggested above.

Feel free to call me if you have any questions or concerns.

Sandra

At our February meeting, Norma-May Isakow was so generous and gave each attendee daffodil bulbs ready to plant. Here are the instructions and a picture of her daffodils blooming. Happy gardening!

Daffodil Bulbs

Thank you to all who took home Tazetta Grand Soleil D'or daffodil bulbs for planting! For more about the Worldwide Daffodil Project, please visit www.daffodilproject.net

I suggest you plant the bulbs in soil in a pot with drainage with roots downward and tips covered. Place the pot in the sun and water sparingly. Hopefully they'll bloom and you'll email me a pic to nmisakow1@gmail.com like this one of my yellow flowering garden at Pinetree Park Community Garden in Miami Beach with Tazettas in the foreground!

So appreciated,

Norma-May

Spring Gardening - April checklist for zones 9-11

From Sandra:

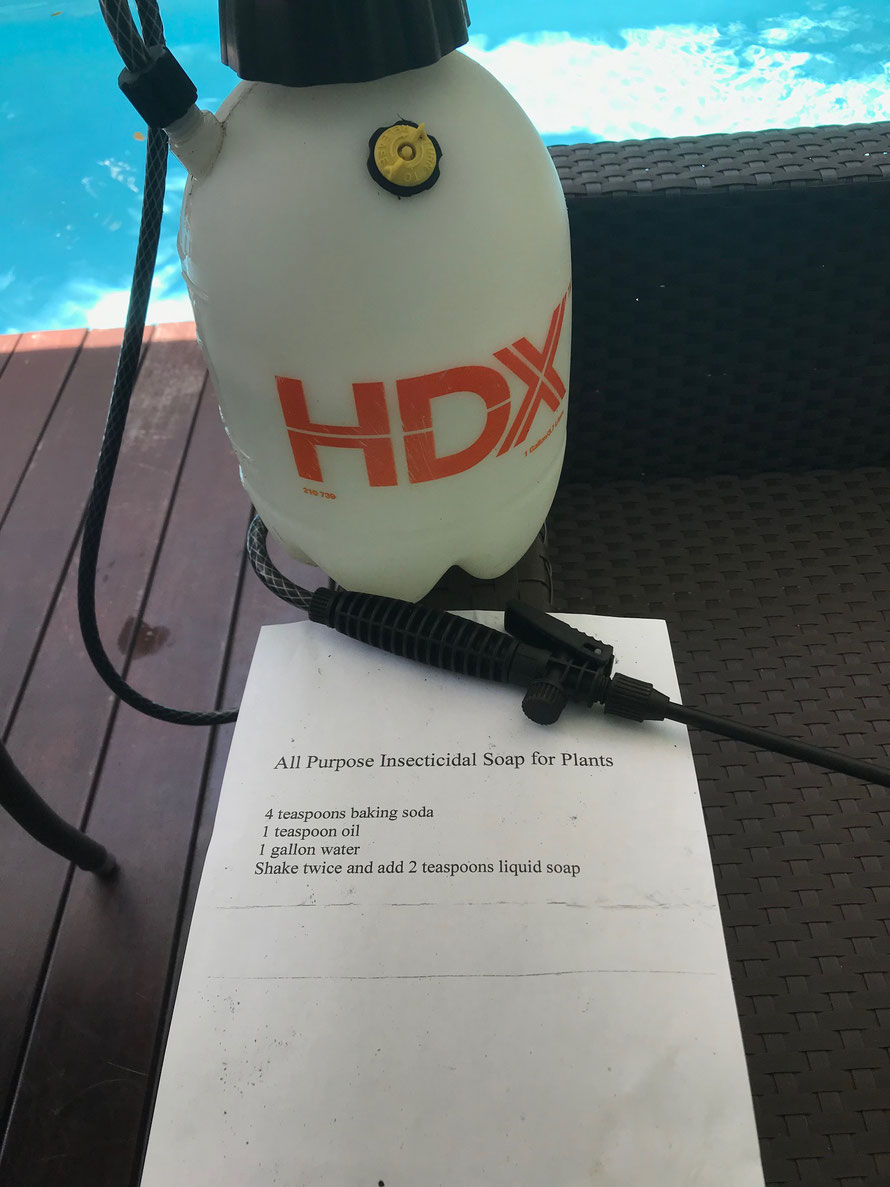

Below are the 2 mixes I use, one for fertilizing palms and shrubs that need a boost, and the other the mix I use on my orchids to keep down the fungus and mites. They are both great!

Fruit gardening by Paulette Johnson

There is a recipe using Canistel in the Recipe tab.

From Gale Patron

I keep a gallon of this on hand always! Credit: Farmer, Joe Esteras, Aibonito, Puerto Rico

Interesting article from the NY Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/realestate/how-and-why-to-use-native-plants.html?referringSource=articleShare

How (and Why) to Use Native Plants

You know they support pollinators and native wildlife, but you may not have a meadow where they’ll feel at home. Here’s what to do.

By Margaret Roach

In recent years, the demand for pollinator plants has surged. But most of us don’t have room for a meadow.

So where do these native plants fit in your garden, which may not be that big and is probably not very wild-looking? And how do you find plants that are native to your particular location, with the highest value to beneficial insects and, in turn, birds and other native wildlife?

One of the first places I saw native plants being cultivated was outside Wilmington, Del., around 1992, at Mt. Cuba Center, a former du Pont family estate that is now a native-focused public garden, with more than 50 acres of display gardens on over 1,000 acres of natural land. It is also a research facility, where large-scale trials are conducted on selected varieties of native annuals, perennials and even shrubs, testing for garden worthiness, disease resistance and appeal to the insects who have evolved alongside the plants.

George Coombs, Mt. Cuba’s director of horticulture and former trial-garden manager, has watched a lot of native plants in action. We discussed some general principles to help gardeners get started finding, and using, the best natives for their location and goals.

Get Oriented — the Way a Plant Does

Although a nursery tag may say “native,” the species could hail from a completely different sort of area. That’s because plants don’t observe state boundaries, but rather habitats within regional zones, like coastal plains or forests with particular soils, light and moisture conditions.

State native-plant societies or organizations like Mt. Cuba can guide gardeners to solid local reference sources, Mr. Coombs said, including ZIP code-based plant databases from the National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation and others.

Decide What You Want to Accomplish

Any native planting can help — at least in a small way — to bridge the gaps in our fragmented, overdeveloped habitat. But what should you emphasize?

“Think about what kind of wildlife you want to attract,” said Mr. Coombs, who has seen up close the appeal of Monarda to butterflies and hummingbirds, and how Baptisia is “a great early-season food source for bumblebees.”

A water garden that remains unfrozen year-round attracts birds, dragonflies and more.

Focus on Welcoming Insects, Rather Than Pretty Plants

Butterfly and moth caterpillars are essential components of food webs that sustain other native creatures, specifically songbirds, many of whom feed the insects to their young. “Grow bugs” is a kind of mantra for habitat-style gardeners, which means using no insecticides or other chemicals.

But Where to Make Room?

In many residential settings, shrinking the lawn — which doesn’t offer pollen, nectar or seed, because we mow it — is a prime opportunity.

I have what I like to think of as “unmown” islands within my garden, creating small meadows of whatever came up (little bluestem grass and goldenrod, mostly), which I then edited. I’ve transformed other grassy areas into planting beds for native trees, shrubs and perennials.

You could also rethink a grass strip along the property line, inside a fence or hedge, that you may currently mow right up to, or that may be planted with nonnative ivy, pachysandra or vinca. Even a six-foot-wide swath transitioned to native ground cover and fruit-bearing shrubs enhances diversity.

Despite having the smallest flowers of all the tall garden phlox trialed at Mt. Cuba, the cultivar Jeana was the most appealing to butterflies. Credit... Mt. Cuba Center

Formal Spaces and Containers Can Hold Natives, Too

At Mt. Cuba, when the estate’s traditional gardens were transformed into native landscapes, it was “a great opportunity to showcase natives in a more traditional, formal setting that a homeowner could adapt in their own landscape,” Mr. Coombs said.

In one spot, long planted with summer garden annuals, the shift to native perennials included plants like Phlox Forever Pink and Echinacea tennesseensis.

Mt. Cuba’s pots are swapped out three times each season with a mix of perennials and shrubs. In spring, a deciduous native azalea in a large container might be surrounded with woodland phlox (Phlox divaricata), purple-leaved heuchera and fringed bleeding heart (Dicentra eximia).

“Last fall, we did pots of Muhlenbergia grass that were stunning,” Mr. Coombs said.

Best of all, the plants can be overwintered in the vegetable garden and used again, or incorporated into the garden.

Plant in Layers, the Way Nature Does

One such opportunity: Enlarge those diversity-lacking mulch circles beneath trees in a lawn, making room for native woodland shrubs as the middle layer, then herbaceous perennials beneath.

“No bare soil,” Mr. Coombs advised. “And your ‘ground cover’ can be three feet tall — that’s fine.”

Even the formal gardens by the estate house at Mt. Cuba have been transformed into native landscapes. In spring, Penstemon Dark Towers, Tradescantia Concord Grape, Gillenia trifoliata Pink Profusion and Artemisia Valerie Finnis show off in the south garden. Credit... Mt. Cuba Center

Plan for a Succession of Blooms

That way, you’ll support more than one moment in native organisms’ lives.

In a mixed ground-cover planting, don’t choose all spring-flowering things and then have nothing on offer later for insects or birds.

“A lot of people go to the garden center in spring and just buy what’s blooming, but it’s important to think about what’s happening later,” Mr. Coombs said. “Go back in September and see plants you didn’t see in the spring.”

Even better: Call ahead with a wish list based on research. “Talk to your garden center about plants you hope to grow and why,” Mr. Coombs said. “In a roundabout way, the more they hear from customers, the more they will stock natives.”

Choose a Diversity of Flower Shapes and Sizes

“A hummingbird plant is very different-looking than a butterfly plant,” Mr. Coombs said, noting that even within a single genus, the size and shape of the flower parts can vary enough to appeal to an entirely different clientele. “In our Coreopsis trials, the species’ different morphological characteristics predicted what type of bee would prefer it — this bee’s tongue would match it, where another’s cannot.”

To figure out which plants pollinators are frequenting, researchers from the University of Delaware, led by Douglas W. Tallamy, have been conducting scientific pollinator studies in the Mt. Cuba trial garden.

In a large trial of Phlox paniculata, tall garden phlox, small turned out to be better.

“The variety called Jeana was the one attracting the most butterflies,” Mr. Coombs said. “But we’re not really quite sure what characteristics were bringing the butterflies in. Its flowers are actually the smallest out of any garden phlox, somewhere between a pea and a dime.”

In fall, the south garden at Mt. Cuba blooms with native perennials, including Solidago sphacelata Golden Fleece, Penstemon Dark Towers, Coreopsis palustris Summer Sunshine, Symphyotrichum laeve Bluebird, Stokesia laevis Peachie’s Pick and Artemisia Valerie Finnis. Credit... Mt. Cuba Center

Not All Cultivars Are Created Equal

To pollinators and other animals that interact with plants after long coevolutionary histories, the closer a variety is to the straight species (as nature’s version of each plant is called), the better.

Breeding changes made to please gardeners, like double flowers, don’t get high ratings. In the smooth hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens), for instance, the popular cultivar Annabelle, a mophead type with mostly sterile bracts, cannot sustain as many insects as the original lace-cap flower arrangement.

Maybe most dramatic: Leaf-color changes made in a cultivar from green to purple or red can be unpalatable to insects that rely on the plant. Red and blue pigments, called anthocyanins, don’t taste as good as chlorophyll.

Manage the Garden Differently

Don’t clean up too obsessively or too soon, especially in the spring and fall, as beneficial creatures need leaf litter and other hiding places to overwinter and reproduce. “We prolong our cutbacks till later winter or early spring — one of the last things we do,” Mr. Coombs said.

And as a compromise between horticulture and ecology, “you can even mulch in place,” he said. “Cut four-foot stems into pieces and let them lie rather than carrying them away to the compost.”

Even for the Pros, It’s an Experiment

“I always tell people that it’s OK to fail,” Mr. Coombs said. “Don’t worry, trial and error is how we create a lot of our gardens at Mt. Cuba. Yes, we may have had a design in mind, but sometimes the garden has its own idea what will grow there and not. You will have to take direction from Mother Nature.”

The American painted lady butterfly, Vanessa virginiensis, enjoys one of the phlox cultivars in the Mt. Cuba trial garden. Credit... Mt. Cuba Center

Resources for Your Research

For area-specific advice, look to your state native-plant society’s website, found on lists provided by the North American Native Plant Society or American Horticultural Society.

ZIP code-based plant-search tools at the Audubon Society and the National Wildlife Federation show what is native where you live. Regional recommended-plant lists at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center or Xerces Society can also help. In New England, try the Native Plant Trust Garden Plant Finder or its GoBotany database.

The Mt. Cuba Trial Garden reports compare cultivars of popular native perennials. Mt. Cuba, like the Native Plant Trust in New England and other regional native-plant nonprofits, offers online classes on identifying and gardening with natives.

Want to really drill in? Most states publish an online flora, a database of plants present in the state, native and not, down to the county level. Some outstanding examples are the New York Flora Atlas and Calflora, for California. (Search for your state’s name and “flora” or “state flora of.”)

“Nature’s Best Hope,” Douglas W. Tallamy’s new book, is a guide to transforming our home landscapes into more diverse places.

The Basics

Nursery tags that say “native” might mean native to the United States, not native to your particular landscape, so the first job is learning what is native to the place where you garden. Consult state native-plant societies, native-plant organizations like Mt. Cuba or ZIP code-based plant databases from the National Audubon Society or the National Wildlife Federation.

Focus on which beneficial insects or birds you want to attract, and learn more about the plants they favor in your area.

Making room for natives in the residential landscape usually means shrinking the lawn. Beds of natives should be planted in layers — tall, medium, shorter — the way nature plants them.

Adding water that’s unfrozen year-round to your landscape and being a little messy — leaving leaf litter in place as long as possible — are other tactics for increasing diversity.